Sometimes it’s interesting to understand the inspiration for a story. If you’re curious about the origins of my story “Charcoal,” published in the Fall 2015 issue of Prairie Schooner, here’s a little about what went into it.

In August of 2011, I attended a screening of the film “Cave of Forgotten Dreams,” a documentary by Werner Herzog about the Chauvet ice age paleolithic cave paintings in France. The film is remarkable, not just because of the subject, but because of Herzog’s treatment of it and his unprecedented access to the cave. I highly recommend the film, which is available on Netfllix and elsewhere.

When I was in elementary school, I wanted to be an archaeologist. In college I took anthropology and archaeology courses, but in the end decided against pursuing it as a career. I still have my amateur fascination with prehistory, so this film held me rapt, until one line of dialogue in the movie pulled me completely out of the cave. I haven’t watched the film again since then, so I don’t know the exact wording, but it was a comment about the security guard or guards stationed outside the cave to keep intruders out.

At that moment, my attention went from the cave to the idea of a security guard for a cave. I couldn’t stop thinking about that job, that person, what a strange way that would be to earn a living. What would it be like to be that person? After the film was over, I remarked to my friends how interested I was in the security guard, and of course they hadn’t even noticed that one tiny, crazy detail. It was not the thrust of the film for anyone in the theater but me. I decided on my way home that I had to try to write a story from the point of view of that security guard.

In September of 2011 I went to Gilman, Illinois for a residency called “Writers in the Heartland,” anxious to start this story. I wrote part of the first draft there. A month or so later, I had a residency at the Virginia Center for Creative Arts and continued to work on the story.

My initial vision of the story was that it would be an exploration of how something profound and moving like 30,000-year-old cave paintings could affect one’s psyche. I could imagine becoming obsessed with the drawings and wanting to possess them, to recreate them, to retreat into one’s own version of what must have been a sacred place for prehistoric people.

Of course, when you write a story, other things creep in. Suddenly my protagonist had a nephew that I hadn’t known about. Their relationship infiltrated the story. In my head, since the Chauvet cave was discovered in the 1990s, that’s when my story was taking place. Also during the 1990s was the founding of the European Union and discussion about globalization, which was kind of a new topic then. I started to think about what happens to jobs during globalization and outsourcing and how a person without much education, like my protagonist, was going to face this new world.

Soon after I returned from VCCA, where I probably revised the story 3-4 times over the three weeks of the residency, I began sending it out to literary journals. TOO SOON! I have a patience problem, a history of sending work out before it’s ready. It was rejected 3 times in that round of submissions. I stopped sending it out, set it aside, and later worked on more revisions until I sent it out again at the beginning of 2013. Fortunately, I use Duotrope to track my submissions, so I can easily look back over the submission history of this story.

My habit is to send a story out too soon, pull back and revise it more, send it out more, revise it again, lather, rinse, repeat. I don’t recommend this method. I still haven’t worked out how to know when a story is finished, but now I know it’s probably not finished when I think it’s finished. “Charcoal” was rejected a total of 23 times over a series of quite imperfect drafts.

Between the end of 2013 and the end of 2014, something about my latest revision was working. The story was a finalist in 4 different contests. I asked friends whether that meant it was close to right, but not quite there, and should I try to “fix” it more. Everyone I asked said that I shouldn’t change it if it was that close so many times. I was sufficiently insecure about my writing that I considered revising it again anyway, but instead decided to send it out again, this time to Prairie Schooner.

Prairie Schooner does not accept simultaneous submissions. I know a lot of writers don’t consider themselves bound by that requirement, but I do. That meant, for the time I was waiting for a response from Prairie Schooner’s editors I couldn’t send it elsewhere and so would not be continuing to revise the story. According to Duotrope, after a wait of 152 days, I received an email from the editors of Prairie Schooner, offering to publish the story, but requesting that I consider revising the ending.

Endings are hard. I have read so many stories that are engaging all the way to the ending and then disappoint. Either they just end, with no feeling of resolution or inevitability, or they wrap things up too neatly. It’s very hard to get an ending that works.

I had always felt the ending was the weakest part of this story. I had changed it several times, mostly in response to readers’ comments. I talked with Kwame Dawes, the editor of Prairie Schooner, about his suggestions for the ending, took a long walk in the woods, made one last draft of the ending and sent it off for publication.

I hope this will give new writers some perspective on publication. This story took about 4 years from inception to print. I don’t know whether there was anything I could have done differently, except to wait longer before submitting it, revising and going back over it over a longer period of time. It might have been rejected fewer times before an editor somewhere liked it and thought it worthy of inclusion in his journal. I’m beginning to get the hang of this, maybe, and beginning to have a little more confidence in my own work. It all takes time, patience, practice, trial and error. Like pretty much everything else in life.

Have a similar story? Share in the comments the length of your favorite stories’ journeys from first draft to publication (print or online).

When it’s used as a verb, I think of “retreat” in a military sense–to go backward to safety. There is an inherent tension between this meaning and the meaning of a writing “retreat,” since the purpose of the latter is to make forward progress. Sometimes in order to make progress, I feel like I have to detach myself from the rest of my life and go somewhere else.

When it’s used as a verb, I think of “retreat” in a military sense–to go backward to safety. There is an inherent tension between this meaning and the meaning of a writing “retreat,” since the purpose of the latter is to make forward progress. Sometimes in order to make progress, I feel like I have to detach myself from the rest of my life and go somewhere else.

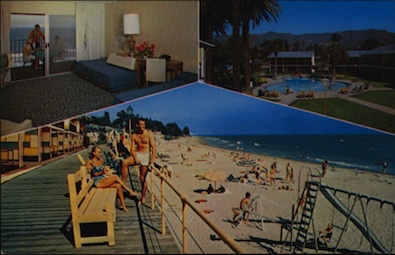

I just received this in the mail from an ebay seller. It’s a postcard from a hotel where I worked in 1980, which is the model for the setting of my second novel, tentatively entitled The Sea View Hotel. It’s not a great title, I know, but I’m not going to worry too much about that now. I say it’s the “model for the setting” because it’s not the exact setting. The setting is my memory of the place with some embellishments. I’ve messed with the geography and the name and a lot of other details in order to make the place fit the story. But it’s nice to have this tangible memory-jog while I’m writing. These photos were taken long before I worked there, but it didn’t change much during that period.

I just received this in the mail from an ebay seller. It’s a postcard from a hotel where I worked in 1980, which is the model for the setting of my second novel, tentatively entitled The Sea View Hotel. It’s not a great title, I know, but I’m not going to worry too much about that now. I say it’s the “model for the setting” because it’s not the exact setting. The setting is my memory of the place with some embellishments. I’ve messed with the geography and the name and a lot of other details in order to make the place fit the story. But it’s nice to have this tangible memory-jog while I’m writing. These photos were taken long before I worked there, but it didn’t change much during that period.